“Co-CEOs are ideal in many situations, especially when the executives provide oversight of each other’s actions and have complementary skill sets,” he explains. “It’s actually a very successful model.”

From his research on more than 100 shared-governance examples, Ferris offers the following highlights: “Job Complementarity” - Of more than 100 shared leadership structures examined in the study, Ferris found that 45 percent had what he calls “job complementarity,” while another 45 percent had “educational complementarity” (i.e. one CEO with a graduate degree in engineering and the other with an MBA or law degree). “Ninety percent of the sample had some complementarity in terms of duties and backgrounds, which allows for a much broader set of experience and ideas with which to chart a strategy or make a decision,” Ferris says. "Compensation Gap" - Another interesting finding—co-CEOs earn a little less than twice what a single CEO would earn. This seems excessive, but Ferris says the expense may be worth it, given differences in the type of compensation. “Co-CEOs get a lot less incentive-type compensation, but equivalent amounts of cash compensation,” he says. “The median co-CEO team receives 35.7 percent of the options of a solitary CEO, which we interpret positively.” The reason a single CEO’s compensation is geared to maximizing shareholder value is to incent the individual to perform. However, with co-CEOs, “There is more of a self-policing aspect in play,” Ferris says. “Each ensures the other works as hard as he or she can to boost results—hence there is less need to link pay to performance.” "Tenure" - A similarity in both leadership models is tenure—a median 4.5 years for co-CEOs and a bit more than a median five years for a sole CEO. Says Ferris, “This tells me that the co-CEO model is working just as well as the CEO model; otherwise we would see a bigger disparity.” Aspen Insurance had been steered by co-CEOs for the past year and one-half; so when the time came for a change at the top of the ladder, the company opted for the same shared governance model.

The reason is simple—the model worked for the diversified provider of insurance and reinsurance products—with assets of $9.3 billion and more than 670 employees in eight countries.

“We were becoming increasingly diverse by geography and products, and it was very hard for one person to cover all the time zones and still maintain the sort of control we wanted to see over the business,” explains Rupert Villers, co-CEO (formerly with John Cavoores).

“John and I got along great, we’ve known each other a long time, we have different skill sets, and we’re both plain speakers. Sometimes people thought we were having a tremendous row, but we were just sorting things out.”

A tremendous row? Does this give pause to Mario Vitale, former CEO of insurance broker Willis North America and Villers’ new teammate?

“I’ve been in shared positions before, though not as a co-CEO,” Vitale says. “If you don’t have a big ego, it can work. They key is to complement each other in terms of strengths. Rupert and I have some overlapping expertise, but a great deal of our experience is diverse—we bring different things to the table. He’ll lead on certain responsibilities and I will on others, which eases the decision-making process.”

Vitale believes two people may be required to run a far-flung global enterprise.

“The world of business is more global and complex, with more regulations and reporting requirements than ever before,” he notes. “That’s a lot of responsibility for one person.”

There is another reason why he is excited about sharing the helm. “For the first time in my career, I can go on a vacation and not take my BlackBerry,” he says. “I know Rupert can handle whatever comes up.”

Aspen Insurance had been steered by co-CEOs for the past year and one-half; so when the time came for a change at the top of the ladder, the company opted for the same shared governance model.

The reason is simple—the model worked for the diversified provider of insurance and reinsurance products—with assets of $9.3 billion and more than 670 employees in eight countries.

“We were becoming increasingly diverse by geography and products, and it was very hard for one person to cover all the time zones and still maintain the sort of control we wanted to see over the business,” explains Rupert Villers, co-CEO (formerly with John Cavoores).

“John and I got along great, we’ve known each other a long time, we have different skill sets, and we’re both plain speakers. Sometimes people thought we were having a tremendous row, but we were just sorting things out.”

A tremendous row? Does this give pause to Mario Vitale, former CEO of insurance broker Willis North America and Villers’ new teammate?

“I’ve been in shared positions before, though not as a co-CEO,” Vitale says. “If you don’t have a big ego, it can work. They key is to complement each other in terms of strengths. Rupert and I have some overlapping expertise, but a great deal of our experience is diverse—we bring different things to the table. He’ll lead on certain responsibilities and I will on others, which eases the decision-making process.”

Vitale believes two people may be required to run a far-flung global enterprise.

“The world of business is more global and complex, with more regulations and reporting requirements than ever before,” he notes. “That’s a lot of responsibility for one person.”

There is another reason why he is excited about sharing the helm. “For the first time in my career, I can go on a vacation and not take my BlackBerry,” he says. “I know Rupert can handle whatever comes up.”

The Market Values Co-CEO Structure

Performance data for 30 companies that transitioned from a traditional single-CEO leadership to a co-CEO structure shows a positive reaction from the market. Given the relative rarity of co-CEO leadership structures, one might expect the market to view them with suspicion. Not so, says Professor Stephen Ferris of the University of Missouri, who has conducted extensive studies of the efficacy of the co-CEO model. “Our research shows that the market reacts positively and significantly to the announcement of a dual CEO appointment,” says Ferris, who crunched the numbers on 30 companies announcing such transitions to get a bead on the market’s response to a co-CEO structure. “The average abnormal announcement return—or the return after adjusting for regular market movement and the firm’s expected return, given its level of risk—after such an announcement was 2.58 percent. If the market didn’t like these arrangements or was indifferent, then the announcement returns would be zero.” The table below presents those findings, as well as the “abnormal announcement” returns for event windows before and after the announcement. “We wanted to look at what happened if the announcement was late in the day and the market couldn’t capture the impact on that first day, as well as what happened if there had been some leakage and people knew the announcement was coming,” explains Ferris. In all cases, the impact was both positive and significant—suggesting the market generally views a co-CEO arrangement as a positive development.Market Performance after Announcement of a Co-CEO Structure

| Event Window | CAAR* |

|---|---|

| Day of Announcement | 2.58% |

| Day of and Day After Announcement | 2.81% |

| Day Before and Day of Announcement | 6.19% |

*CAAR = cumulative average abnormal return

Too Many Cooks

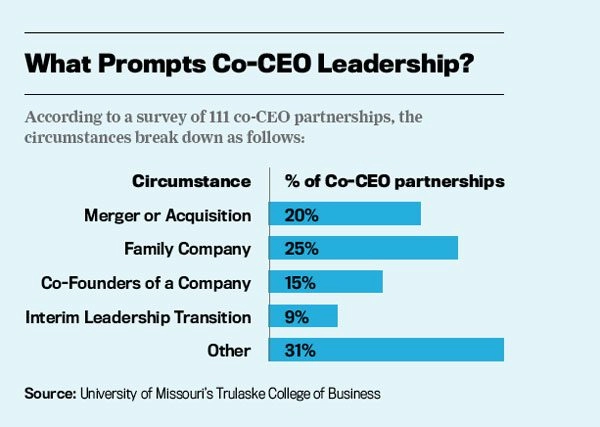

What Prompts Co-CEO Leadership?

According to a survey of 111 co-CEO partnerships, the circumstances break down as follows: